Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can require large amounts of computer time and memory. This is especially true in simulations of solid lattices of atoms, since elastic strains extend long distances and capturing the effects can require millions or billions of atoms. The GFMD method is a mathematically and conceptually elegant simulation technique that can dramatically help.

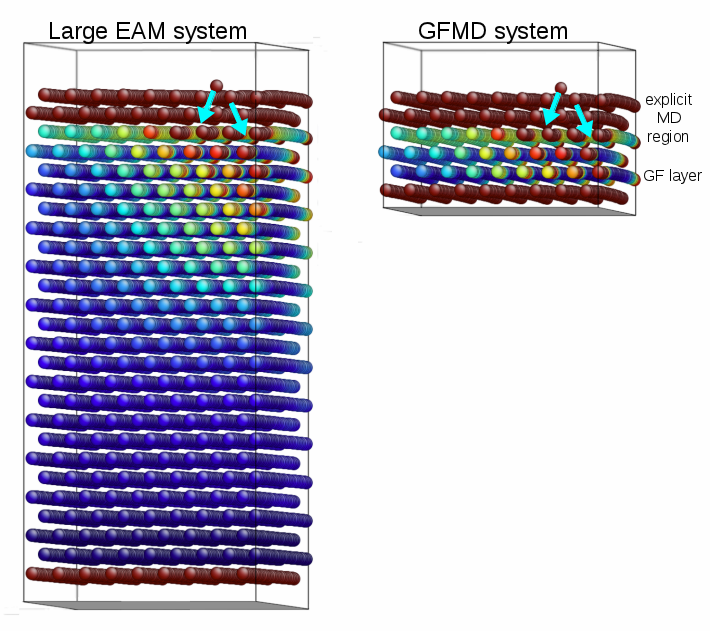

GFMD stands for Greens Function Molecular Dynamics. The method uses a function called the static surface Greens function (GF) of the material. The concept will be described more in the next paragraph. Importantly, the GF essentially contains all the information about the linear behavior of the lattice without having to simulate the lattice. What it means is that regions of the atomic lattice with small strains can be deleted from the simulation, and the single layer of atoms at the boundary of the region can be controlled in a more complicated way. Being able to discard those large regions of the lattice means that the simulation reaps large savings in memory and CPU time.

Campañá and Müser [1] introduced GFMD and showed how the method can be naturally used in molecular dynamics. Our first paper rigorously developed GFMD based on the atomic interactions of lattice of molecules, making it an elegant and seamless boundary for MD simulations [2]. Our second paper (in preprint) extends GFMD to realistic, many-body interactions between atoms–which can be very slow and benefit the most from the speed-up [3].

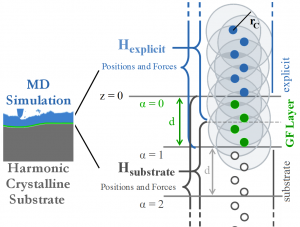

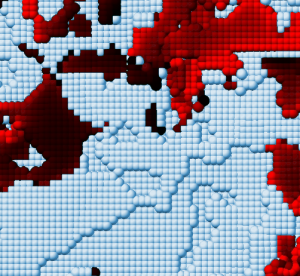

To give an idea of the technical underpinning, we describe a few more details of the method. The idea is that, as long as the strain is small, the atomic interactions can be considered at linear order. In simulations of friction, for instance, large plastic strains occur near the surface of a solid, where a full, explicit, MD simulation must be used. But further away from the surface, the Hamiltonian of the system can be approximated to quadratic order in the atomic positions.

The first and second derivatives of the Hamiltonian compose the external forces and dynamical matrix of the atoms, and, given that the atoms form a regular crystalline structure, transfer function methods may be used to calculate the GF. The surface GF is nothing other than the equilibrium displacements of the surface atoms when the surface is subject to a point force. Given the linearized Hamiltonian, the effect of an arbitrary exerted force on the surface is given by the the super-position of the GF displacements.

For many-body potentials, complications arise. False forces are generated, so called ghost forces, at the layer of atoms that connects the explicit region from the linearized substrate. Also, the forces cannot be decomposed into having a single-atom source, complicating implementation into standard MD codes. Meticulous attention to the formalism and familiarity with MD codes allowed us to introduce the appropriate domain decomposition, into explicit, substrate, and GFMD layers.

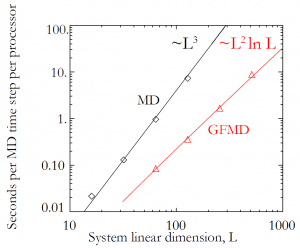

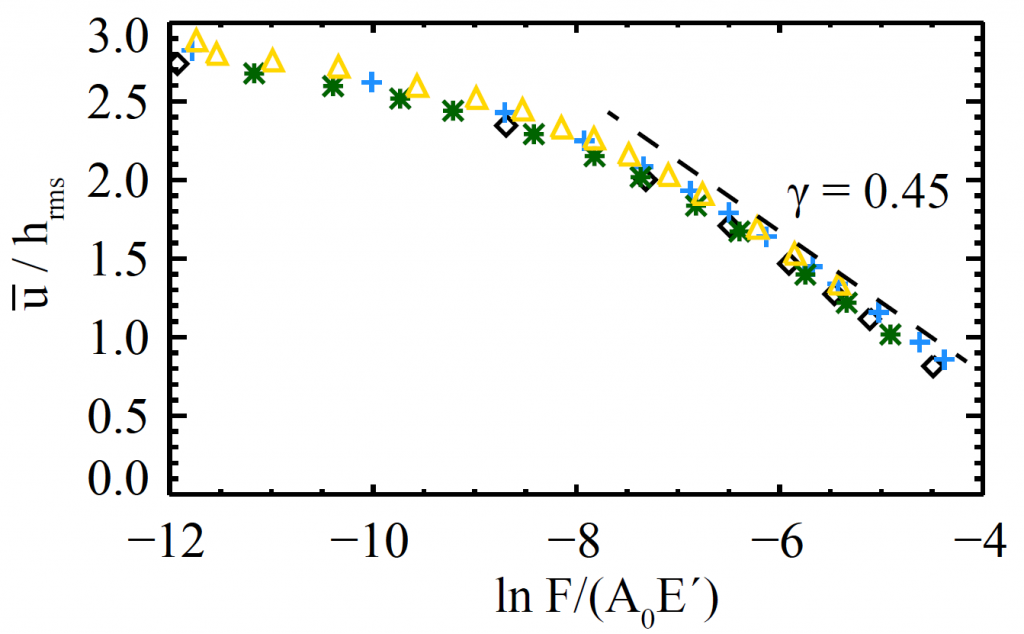

This detailed work results in a dramatically faster code. The plot at the top of this post indicates the speed up from running GFMD as opposed to the full system. The time per simulation time step scales with system size as

rather than

. Furthermore, the system is comprised of far fewer atoms, and so energy minimization requires fewer time steps.

[1] Campañá, Carlos, and Martin H. Müser. “Practical Green’s function approach to the simulation of elastic semi-infinite solids.” Physical Review B 74.7 (2006): 075420. https://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.74.075420

[2] Pastewka, Lars, Tristan A. Sharp, and Mark O. Robbins. “Seamless elastic boundaries for atomistic calculations.” Physical Review B 86.7 (2012): 075459. https://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.86.075459

[3] Sharp, Tristan A., Lars Pastewka, and Mark O. Robbins. “Green’s function molecular dynamics with multi-body interactions.” In preparation (preprint available upon request).