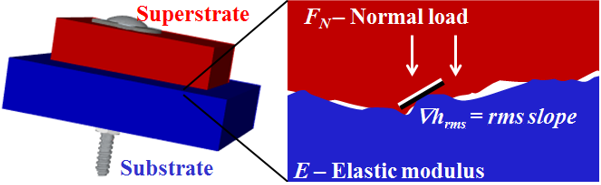

Essentially all materials have rough surfaces at small scales. This can be a problem for engineers designing electrical contacts, thermal contacts, or seals to prevent leaks, since the roughness creates gaps between the two contacting surfaces. By increasing the pressure, the two solids can be forced closer together, reducing the gaps somewhat, but some space between the surfaces usually still remains.

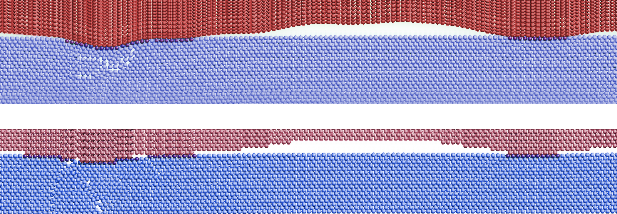

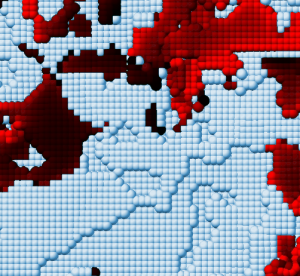

Work with Mark O. Robbins quantified how surprisingly resilient the gaps are, and how important they are in determining the contact properties. To analyze the problem, we had to overcome technical challenges related to the large range of length scales of random-rough geometry on typical material surfaces, usually millimeters down to atomic scales. The rough geometry can be modeled using the mathematics of random (self-affine) fractals. Large-scale parallel processing on a computing cluster is required to simulate and analyze contact between many random realizations of rough 3D cubes of length 1000 atoms on a side. We worked with Lars Pastewka to write C++ code for GPUs to do fast simulations using lattice Greens functions and continuum-elastic Greens functions, which will be described in a later post.

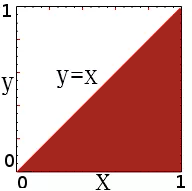

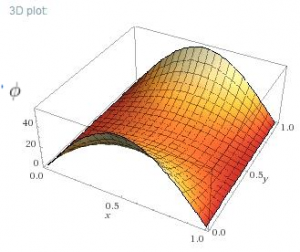

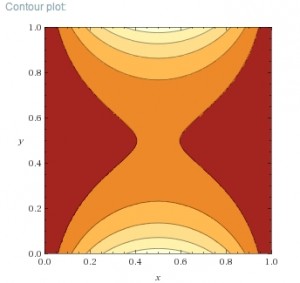

We found that the large-scale features of the material’s surface get flattened more easily, but the small-scale roughness cannot be squeezed away even at considerable pressures; we found that the fraction of the surface that is in contact is well-defined and at common pressures is less than 20%. Within this regime the fractional contact area obeys a simple law: , where

is the confining pressure,

is the material’s contact modulus,

is the effective Poisson ratio,

is the material’s Young’s modulus, and

is the root-mean-squared slope of the original roughness profile[1].

is a dimensionless constant with value about 2.2.

We considered this problem with both continuum-scale and atomic-scale simulations. We found that the continuum results can often be applied to small scales, meaning that continuum analyses are often appropriate for nanotechnology applications[2]. At the atomic-scale, the concept of contact area gets replaced by the number of atoms that exert repulsive forces on the other surface. However, for very rough or crystalline surfaces, atomic-scale plasticity causes the value of in the above equation to increase, up to a value of 10.0. We went on to analyze the transition from elastic to plastic contact with roughness.

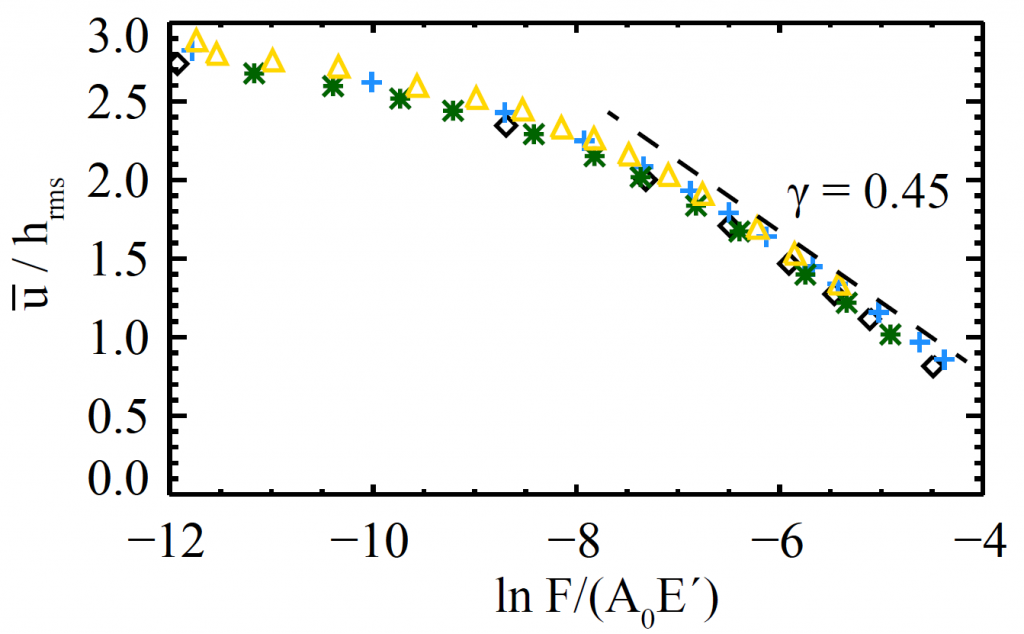

Even if the contacting materials are very stiff, they can seem much less so because of the gap from roughness at the contacting surface; the rough topography can be compressed more easily than the solid material. For both atomic and continuum analyses, the average gap width, decreases slowly with force. We quantified this and showed that at large confining force,

, it follows

where

is the root-mean-squared height of the original surface,

is the apparent surface area. As a result, the stiffness of the interface is

. The stiffness of the interface is extremely low when there is no confining pressure, and so the surface roughness dominates the mechanical response of the whole two-block system.

References:

Chapter 5 of my thesis (papers in preparation)

Sampling of the related work that helped build up this picture:

Hyun, S., et al. "Finite-element analysis of contact between elastic self-affine surfaces." Physical Review E 70.2 (2004): 026117. Pei, L., et al. "Finite element modeling of elasto-plastic contact between rough surfaces." Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 53.11 (2005): 2385-2409. Cheng, S. & Robbins, M.O. "Defining contact at the atomic scale." Tribol Lett (2010) 39: 329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-010-9682-5 C Yang and B N J Persson 2008 J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 20 215214 http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0953-8984/20/21/215214/ Persson, B. N. J. "Relation between interfacial separation and load: a general theory of contact mechanics." Physical review letters 99.12 (2007): 125502. Mo, Yifei, Kevin T. Turner, and Izabela Szlufarska. "Friction laws at the nanoscale." Nature 457.7233 (2009): 1116.